A warrior and a mother

It's International Women's Day, and I'm thinking about how survivors of sex trafficking have made me a better woman.

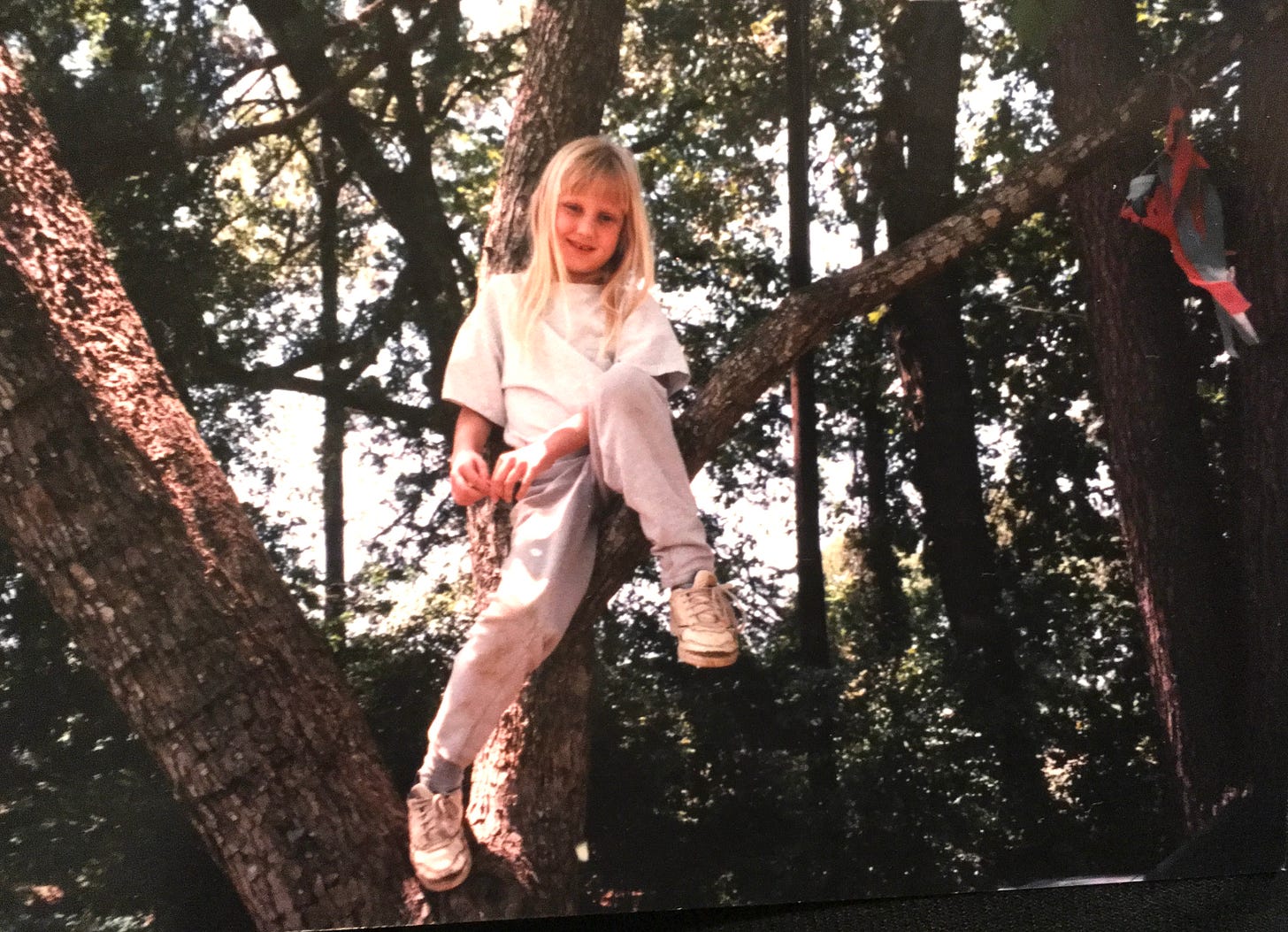

I was 7 when they asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and I confidently declared: “A warrior!”

In the world I lived in, there was only one path open to anyone born in a girl’s body. So I was told: “But how will you do that and be a mother?”

I tried to reconcile these two things: the power I wanted to claim and the expectations of me.

“I’m going to be a mother AND a warrior,” I amended determinedly.

My primary work is serving as Senior Content Manager for a global anti-trafficking organization. That means I tell a lot of stories about some of the most horrific violations humans can inflict on each other— and much of that violence is gender-based. Globally, 54% of those who are in exploitive labor, sex trafficking, and forced marriages are women and girls.

I had the great privilege of coming into my organization right as they were starting to provide more robust aftercare for survivors of human trafficking. This aligned beautifully with my core value in this work: to decenter myself and to recenter survivors, wherever possible.

What this means in practice is that I get to meet some of the most profoundly resilient women in the world. They have been my teachers and guides in learning what recovery looks like.

I want to be so careful, so gentle, so I do not give the impression that these women are somehow more than human. The reality is that they are exactly, fully human. They are us, often in a uniquely revealed form due to the revelatory force of what they have experienced and what they have chosen to do with it.

The impact on me has been earth-shattering.

Some of the best days of my entire life were the days that I spent at a couple of aftercare homes in Southeast Asia. This allowed me to simply be present with survivors, young women who are courageously re-shaping their stories into so much more than the worst things that have happened to them.

When we arrived at the aftercare home, the girls met us with red roses (my favorite) and served us coffee (also my favorite). I’ve kept the ribbon ever since.

I wanted to be a student, to learn as much as I could. I wanted to be a witness. They were so generous with their selves, so recklessly compassionate in the way that they allowed me to be present. I hope I never stop realizing what a gift it is when a teenage girl who doesn’t even speak my language sits beside me and tells the truth.

When I think of the strength that women can contain, I think about a 14-year-old girl who I met in a slum. I think about riding together in our team’s van. I think about the way that she rolled the window half down and leaned out, just enough that the wind caught her hair. Leaning into the fresh air was this small, physical way of leaning into a sensation of movement, of joy.

Our team and law enforcement had already removed her from exploitation twice.

She hadn’t given up.

For every survivor that I have had the chance to speak to, whether in person or via video call, there are dozens more that I get to write about. I will never meet most of them. But I see their photos. I read their case files, often seeing the details of how they actively participated in their exit from exploitation.

I try to steward these stories well. I learn from every single one.

Doing this work has forever changed my understanding of what it means to be a woman. Learning from the deep humanity of survivors’ experience has taught me to look for it in everyone else. All of us have survived something unspeakable. All of us are just trying to stumble our way to hope.

And I have learned that as a woman, I have something to bring to this particular work. For so many survivors who have been through sexual exploitation or other kinds of gender-based oppression, simply the presence of men is a trigger and a threat. I get to show up and say, just by being present: you’re safe. You’re safe with me.

I have witnessed so many of my colleagues wield this power well. The staff at our aftercare home in Asia are incredible. I have learned so much through simply soaking in their tenacious love.

I often think about the declaration of my 7-year-old self, what she wanted to be when she grew up. There weren’t exactly standard career paths laid out for becoming a warrior. But maybe I found one anyway, accidentally. My words are protective forces. And, as I have learned intimately in the past year, they are dangerous to the darkness.

I hold that responsibility in weighty awareness. They say, “choose your battles.” I’ve chosen this one.

And to the other part of my declaration? I will never be a mother — not in the traditional sense. That’s both by choice and because my broken body is not capable of carrying children.

But the social worker for my organization in India once said: “There are so many ways to be a mother.”

I think about it constantly. Yes, my words are weapons. But I hope that I’m more than a warrior. I hope there is something of a transcendent mothering in the compassion I aspire to. I hope that I can show up with a nurturance that births the presence of peace.

I used to shy away from sharing any of my own history of trauma with the people I work alongside, worrying that it would come across as me equating my experience with theirs. I have increasingly leaned into it (terrifying as it is). I know that I have an opportunity to say, “I see you. I hear you. You’re not alone.”

This International Women’s Day, I want to offer a shout-out to the mothers and the warriors. To the women changing the world by surviving it, against all odds. Thank you for being with me. Thank you for showing me what it is to fight and to love.

If you want to join me in the work I do, I invite you to start here: theexodusroad.com/freedom-collective-2024

There are so many ways to be a warrior, and many ways to be a mother. You're doing difficult, but amazing work.

“There are so many ways to be a mother.” I love this because I love being a witchy auntie to all of my friends' kids.