Maybe every hometown is a ghost town, a haunted monument to the selves we left behind.

This past week I stood on the bank of the Cumberland River in Nashville, tears sharp in my eyes, hands clenching and unclenching at my sides.

“You got out,” I whispered to a past self, to a 25-year-old Mary who watched a hundred sunsets standing there, transfixed by her nameless heartache. “You need to know that you got out.”

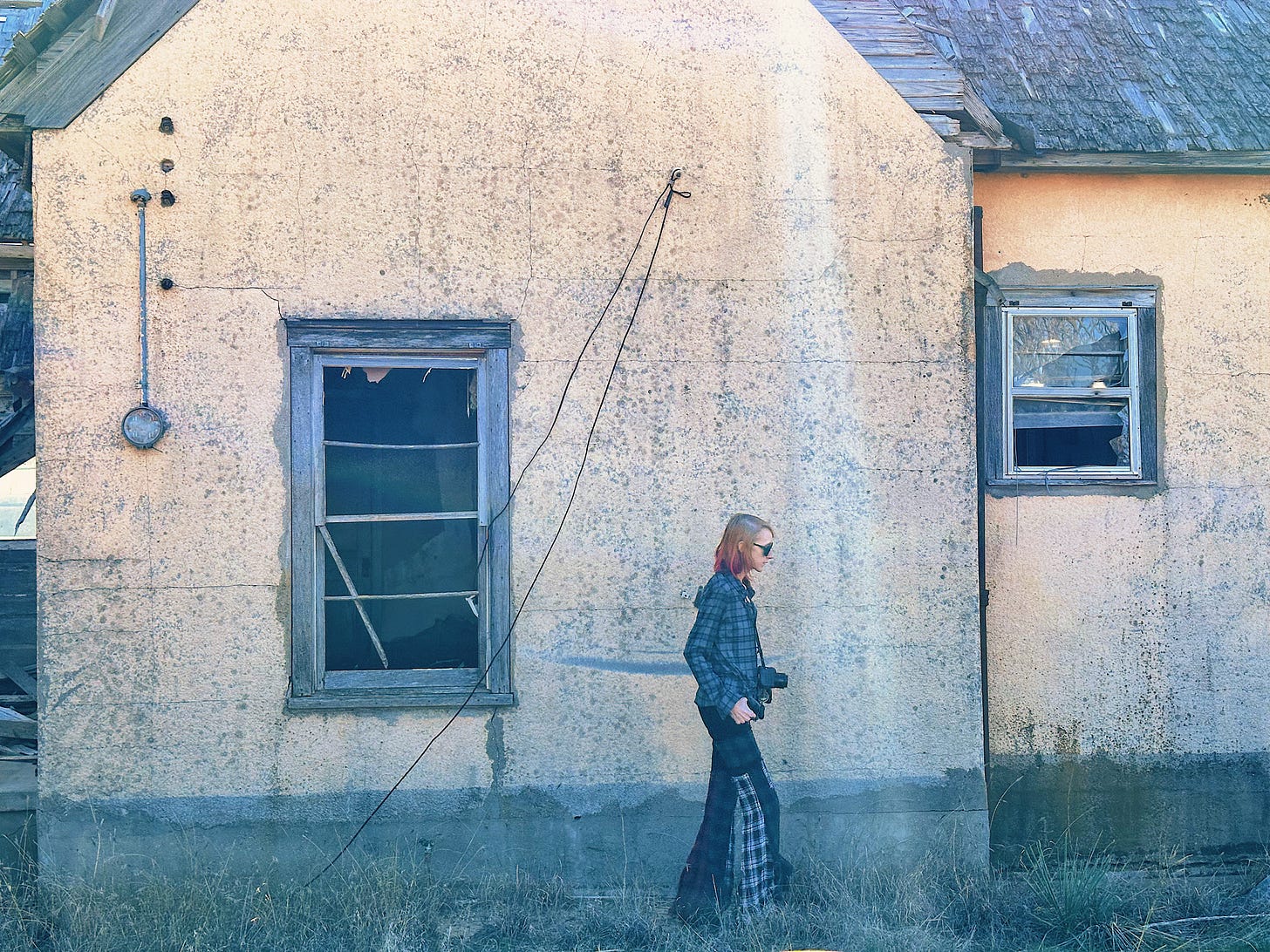

In the past two weeks, I’ve visited the two states I lived in for the longest: Texas and Tennessee. The drive between Texas and Colorado is a desolate one, pockmarked with buildings abandoned during the dust bowl — during the Great Depression or shortly thereafter. I often stop at these houses, compelled by the same fascination that drives me to explore ghost towns in once-rich mining regions of Colorado. I am fascinated by the somber memorials to lives once lived.

“'Cause blood is thick but water is forever

And I'm stiffer than a board, lighter than a feather

And that girl will be a problem only if you let her

And I left her back home but I cannot forget her.”— Halsey

This time around, I stopped at a house I’ve been seeing for years. It had clearly been abandoned with most of its furniture still inside. A mattress’s cloth covering has dissolved off the rusted springs. Tables slant, crotchety creatures lowering towards the floor. The floor gapes with fissures. Texas sun wraps its fingers around the slipping shingles of the roof, prying the building apart.

I felt the symbolism deeply while I cautiously hopped a decrepit fence and peered in the windows, an interloper, a trespasser. I was both the haunter and the haunted, drifting through this old landscape, quieted by the remnants of its past.

Texas always feels that way to me. I can never quite forget what it was like to be young and afraid, desperate to leave my hometown, convinced I never would.

We usually relegate the need to leave where you came from to a kind of juvenile pop punk malaise. But truthfully, that need felt unspeakably urgent to me when I was young. I had lived lifetimes by the day I left home at 21. I was too haunted by all the selves I’d been.

My feelings about Tennessee were more complicated. I built a life for myself in Nashville and then Memphis, scraping it out of the barren ground with my fingernails, spit-shining it into something valuable. It was impossibly hard. I had some of the most profound highs and the most devastating lows of my life during those years. I remember being 25, at the top of my chosen career at the time, relatively healthy in body— and living with rampant undiagnosed PTSD and in utter denial about some extreme abuse. So often, I was told I should be grateful for the glamor of my life. So often, I felt guilty for the pain I was suppressing, all the broken selves I hid.

Is this it? I used to think, listening to people enthuse about the surface level of my experience. Maybe they’re right and I’ve peaked. This is the best it will ever get for me.

I’m so glad I was so wrong.

It was a week after visiting the abandoned house in Texas that I stood beside our old apartment in Nashville. I went for a walk in the neighborhood, quietly conversing with my ghosts. Gentrification has hit the area hard: lots have been subdivided to fit two townhomes each. There’s a bagel shop, a children’s boutique, a highbrow gym.

It was where I once lived, but it also wasn’t. I learned long ago: once you leave your hometown, you can really never go back again. The town will change. So will you. There will never again be that same combination of who you are and what the place was.

Something I’ve learned through repeated visits to places I once lived is that it does no good to either avoid your past selves or to get so lost in them that you forget you’re alive here, now. You have to allow yourself to be possessed by the ghosts of yourself, to carry them all with you.

I have done a lot of therapeutic work over the last year and a half in the Internal Family Systems modality. This model works with the understanding that our psyche consists of different parts, coexisting in an interdependent ecosystem. Those parts have different needs and wants, and sometimes they can contradict each other— just like members of a family.

I thought about that as I scuffed my shoes along a repaved sidewalk where I used to run (and occasionally trip over now-smoothed cracks).

The reality is, our past selves are always with us. We don’t have to go to our hometowns to find them. This is one of those irritating side effects of being human: we cannot escape ourselves. We can never evacuate our own skin. No one else can ever really crawl inside it with us either. We must occupy ourselves, and we must do it alone.

My body is the ultimate haunted house, the essential hometown I’d give anything to drive away from. I have heard a friend say that when you are a trauma survivor, your body is the scene of the crime. You live wrapped in caution tape, outlined by chalk tracing where parts of you died.

I left Texas in 2012. I left Tennessee in 2020. I’ve been trying to leave my body since I was a child— and I haven’t quite managed it yet, despite some seriously over-achieving efforts.

Poem written 12-25-21

My body is a haunted house

crippled by the lives I’ll never live.

No painless passage for sound waves

down the hallways of my ears.

No steady breath of calm

while drifting off to sleep.

No, I will creak and groan

with apparitions of almost,

almost well,

almost whole,

almost real.

As I haunted my past life, I spoke to the past self I carry with me always, the one that is activated by trauma responses and flashbacks. I told her about finding work in a second career where I truly felt purpose and came to see my worth. I told her about the shifts in relationships. I told her about finally moving to Colorado. I told her that one day, she’ll meet two nieces who will be the whole entire Sun and Moon.

I don’t have to revisit physical places to acknowledge frightened past versions of me. But being there in person did help force the matter, make it real, bring to the fore the pieces of me I’m usually frantically trying to escape.

I’ve come to love both Texas and Tennessee. I love the beauty I searched for there. I love the reminder of what I survived. They’re haunted, sure— but with each year that goes by, I get a little better at befriending the ghosts.

And maybe it’s all training ground. Maybe someday I can look at this body, this crime scene, and say gently “I have lived here, and it has changed me” — accepting that without judgment or dismay.

I’m not there yet. But every ghost town I learn to walk through with love brings me closer.

“Even with the cracks in the mirror

My reflection's getting clearer

And I'm trying to cope, at the end of my rope

While I'm doing the best that I can

To live with the broken pieces of me

That were shattered, can't stop the bleeding

I'll never get over it, it's hard to move on

But I'm learning to live

With the pieces of me.”— Daughtry