The carpet ground against the skin of my face, my hip bone stabbing into the floor. I shuddered, uncontrolled spasms of panic rolling through my body. A white plastic hanger lay beside me, snapped in two; I’d unsuccessfully tried to use it to create a sharp edge to release some of the unbearable pressure.

A nurse walked in, her tread soft, her voice gentle: “Mary, do you think you could come to dinner? Everyone else has already gone to the dining room.”

I couldn’t stop trembling, but I choked out: “I can try.”

I struggled to my feet, straightening out my oversized hoodie. I was receiving inpatient care for Anorexia Nervosa for the first time. It felt like I was in hell. It felt like treatment was infinitely worse than the illness.

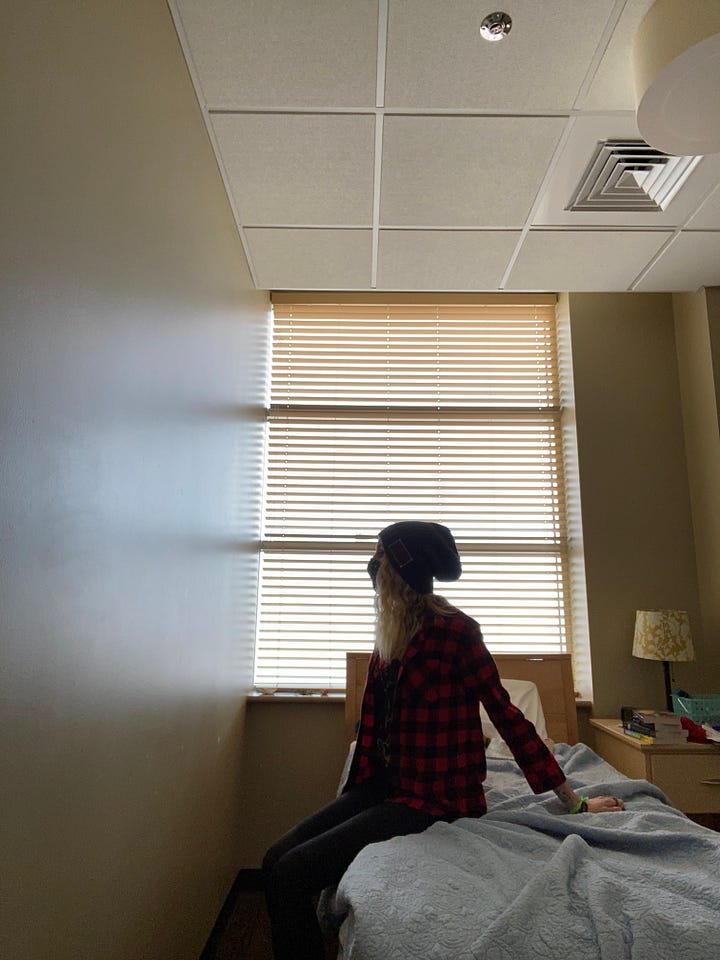

That first stay happened during the peak of lockdown for COVID-19. I watched the world changing through a phone screen, sitting on my plastic hospital mattress. I lost the first of many birthdays and wedding anniversaries to isolation.

I woke up at 5:50 a.m. every morning to the same routine: put on a brittle paper hospital gown. Join the ghostly line of fellow patients in the bathrooms. Pee in a cup. Do a jumping jack to prove I wasn’t hiding anything under the gown to falsify my weight. Step backwards on a scale. Shuffle my way to the nurse’s station to have my blood pressure, pulse, and blood oxygen taken while lying, sitting, and standing. Move to the med window to pick up a plastic cup of pills and have my blood glucose checked.

The process was profoundly dehumanizing. The first week, I woke up every morning and felt tears sting the corners of my eyes — utterly desolate when I remembered where I was, that the rhythm of my day would be one of facing an endless parade of degrading physical pain, the psychologically torturous process of eating foods I have no choice in and am pathologically terrified of, surrounded by strangers, all under the surveillance of stern nursing staff.

Everything fell to pieces

When my eyes met yours

In that hospital gown

And the dreams we once were dreaming

That we held so close

Felt impossible now

And all the plans we held for the future

And all the memories up from the past

The world I once knew

Was in a cardboard box

In the lobby lost and found.

— Switchfoot

Here is something I have learned while spending a combined 12 months out of 4 years in inpatient, residential, partial hospitalization, and intensive outpatient care: it’s possible for something to be both life-saving and intensely traumatic.

I know I am not alone in this. Medical trauma is one of the least-discussed wounds, despite being so prevalent in a society where our supposed healing structures so often harm. We are told we should be grateful just to be receiving care. There is so little room for the both/and of it, the truth that it’s OK to be grateful for the privilege of healthcare and to deeply desire compassion while receiving it.

To be hospitalized for anorexia feels a little like falling down the rabbit hole into a perverse Wonderland. The sterility, the dehumanizing bleakness, the sense of alternate reality, is impossible to capture in words.

Every single bite you eat is monitored and policed, and you can be chastised like a child for not scraping your plate clean, for taking the wrong bite sizes, for putting your hands in your lap.

You have a tech or a nurse standing outside the cracked-open door whenever you use the bathroom, subject to the humiliating process of having them check the toilet and flush for you to ensure you haven’t thrown up.

You have almost no privacy, no time alone, and little to no access to going outdoors— you might go weeks without ever seeing the sky.

Every bodily function is monitored, charted, quantified, placed under the exacting categories that the insurance companies dictate.

While in that place of loss of autonomy, you face every one of your worst fears: the foods that your brain sees as immensely dangerous. Having your body sculpted, changed, reshaped against your will as weight is agonizingly added to the frame you’ve worked so hard to whittle away toward safety.

Refeeding, as they call it, causes excruciating physical symptoms — everything from intense, stabbing abdominal pain to crippling nausea. Electrolytes can shift in a breath, putting your heart function at risk. Dizziness testifies to the hypoglycemia, the hypotension, the litany of side effects that often get worse before they get better. The discomfort is constant. Your body becomes a foreign land. You are a stranger to yourself. There is no distraction from the reality of your utter loss of control, the scream of the disordered cognitions on loop in your brain.

I have a deeply-rooted disgust around the concept of existing in a body at all, and I often assuage that disgust and horror by limiting my food intake, by conquering bodily needs. It’s a cruel reality that trying to stem the downward spiral of an eating disorder is a viscerally physical process, constantly reminding you of your body’s existence.

Then there is the unfeelingness of the system itself. I have had many experiences in the treatment process of professionals refusing to listen to me, reducing me to an illness, trapping me in the four walls of a treatment center and threatening to nullify insurance coverage if I try to leave. I have had my clinically underweight status taken as carte blanche by professionals to suspend my right to consent. I have had my instincts undermined, my requests denied. I have been infantilized, ignored, treated with suspicion even as I am desperately trying to submit and save my own life.

We could sail on broken driftwood through the sopping wet terrain

And count the buildings and the bodies getting swallowed by the rain

And in the water, there's the doctor who didn't listen to my claim

What a shame, he's circling a drain.

— Halsey

All of it is custom-fitted torture for someone whose anorexia stems from trying to self-protectively raise my hands as a shield in the face of lost autonomy and violated selfhood. It has also been deeply difficult personally given that I grew up without access to healthcare, and thus had debilitating medical anxiety well into my 20s— anxiety that still presents itself sometimes as utter nervous system lockdown.

And I am one of the lucky ones: I present as a very compliant patient, which means I’ve never fared as poorly as some of my friends who do not tend to be sick in as acceptable ways as I am.

After a particularly retraumatizing experience in 2022 where a misalignment with clinical decisions made about my case led to extreme activation of my PTSD, leaving me utterly debilitated when I got home, I swore I’d never do it again. I would rather die than let the treatment system ruin me, break my body and spirit.

Going back in 2023 when I was in critical danger was one of the hardest things I have ever done. I cannot begin to explain the cost of keeping myself alive. I bought my life at a price; I pay the resulting tax of nightmares in a relentless weekly rhythm.

I write this at the end of a year in which I spent less time receiving inpatient treatment than any year since 2019. I was hospitalized for 3 weeks in November, just to do the bare minimum to stabilize me after I had significantly deteriorated again. I am in a position now where my core team is committed to managing my multiple chronic conditions outpatient as much as possible, understanding the real harm that constant hospitalization has done to my life and my psyche.

As I have shared before, I am what is known as a Severe and Enduring case— meaning, no one expects at this point that I will recover fully. Though I do hold quite a bit of hope for improvement over time, much damage is objectively irreversible, and I am most likely going to be some level of sick forever. With that being the case, the goal is to figure out how to help me have as full of a life as possible while unwell.

I talk a lot about caring not only about the quantity of my life (measured in days) but the quality of that life (measured in adventure, in wonder, in love).

The clinical team during my most recent hospitalization was one of the most considerate, autonomy-honoring groups of professionals I have ever encountered. I was able to go to one of the very few research hospitals in the country that specializes in cases like mine. They looked at my life, the way I have kept it so full despite my sickness. They told me I don’t need to be in a hospital or a treatment center, beating the dead horse of clinical approaches my body and brain clearly don’t respond to.

I need to live.

Every hospitalization has felt like a kind of baptism: the death of selfhood. The submerging in the murk of an unfeeling medical system. The clawing to the surface, screaming for rebirth.

During my stay last month, as I lay in a hospital bed and felt my heart burn like an ember in my shivering chest, I began to realize: I do not fear it in the way I once did. Resurrection has become muscle memory for this stubborn soul. I have gone under enough times to know I can kick my way to the surface.

But I also hope these gaps between stays continue to lengthen. I hope my confidence in the team I have found right now continues to prove well-founded. And I hope I can continue to be part of advocating for a system that might one day be kinder to all of us.

This essay hit me at a difficult point, and I appreciate your perspective here. My 12 year old son has a severe functional neurological disorder and was hospitalized for a week a year ago. He has been recommended for a two to four week stint of in patient rehab and has been adamant that he does not want to go back, that he hates hospitals, and has started crying and gets very upset about it. Reading this helped me understand better his preselect I've on it, so thank you.

Thank you so much for sharing this. As someone who has h define many inpatient stays, I feel like there’s a world of abuse that society doesn’t know about.