When I was healthy: Easter birthdays

I'm sitting in the parallels of birthdays marking resurrection.

“And now I've faded, don't know why I'm jaded

This is not what I was sent here to do

When I was healthy, I used to be lovely

Now I'm in the bathroom wasting my youth.”

When I first heard those lyrics to a new song by New Zealand artist Robinson, they truly stole my breath, sparking tears in the corners of my eyes.

When I was healthy, I used to be lovely.

I know what she means.

The last time my birthday fell on Easter weekend was in 2019, when I turned 28. It was Easter Sunday exactly that year; this year, it’s on Easter Monday. I have always found it immensely meaningful when these events coincide. The theme of life and death, of entering the heart of the shadow and rising fully alive, is one that sits at the core of who I am. This year, my Easter birthday feels like an affirmation of all I’ve survived, all the valleys of the shadow of death I have walked through to be here.

But life and death felt very different on my last Easter birthday.

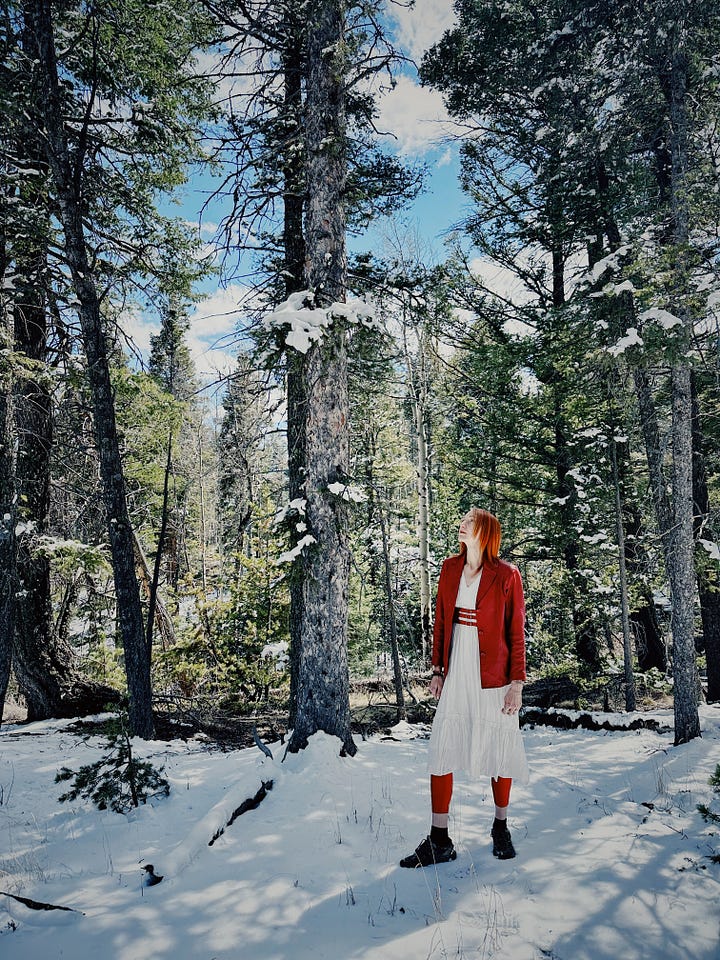

I was visiting Texas in 2019. I couldn’t know it then, but two weeks later, a final trauma would break the already fracturing dam and lead to an anorexia relapse that has been my reality ever since. The photos taken of me on my 28th birthday are some of the very last photos taken of me while I was healthy, before my heart weakened, my bones thinned, my blood became a wasteland.

But behind the smiles my two younger sisters coaxed out of me in those photos, the reality is this: I was sick in another way.

I had allowed myself to become immensely isolated from my safest people, throwing myself into situations where I was used and abused again and again. I was going through several of the most profound personal losses of my life. I was living totally isolated in Memphis. I was dealing with a brand-new neurological condition that was quickly becoming chronic. I had lost my dream job in a devastating implosion, and I was working contracts that didn’t feel like me at all in order to stay financially stable. I had utterly lost my sense of selfhood.

We lived by train tracks in Memphis. I tell the story often that in those long insomnia nights, I’d lie awake and listen to the furious clatter of wheels on steel, imagine myself between them.

I lived in those days with a razor in my wallet to take the edge off the world as needed. When I started starving again, it was because I am hopelessly addicted to the truth. I can’t not tell the truth. But I hadn’t been telling the truth with my voice in those days, not even to myself.

But my truth will be told, whether I want it to or not. So my scars and my disappearing-act of a body began to speak the story instead.

All of it brings me to the question: what does it mean to be healthy, anyway?

I can look at the body I had, the one that mostly did what I asked. But when I think about the dishonesty of that body, I’m not sure it’s something to strive for.

Clinicians have asked me so many times: “you were kind of stable for a while in your 20s. What did you do then? Can you just do it again?”

What I did then was harm myself in other ways. I harmed myself in utter self-abandonment, in isolation, in repressing my values, in staying for far too long in situations that were just as likely to kill me as my eating disorder has been.

The last time I was in the hospital, one of my lifelong friends drove out to see me. He signed me out of the ward— me, wearing my hospital bracelet and grey skin, but determinedly sustaining my life all over again. Later, he signed me back in and sat with me in my hospital room.

Hesitantly, I admitted to him: I don’t want to go back to who I was in my 20s, what I did to survive back then. I would take a sick body and a sound soul any day, even though I am so often asked to emulate how I used to behave.

He looked at me with a certainty I’ve always been grateful for. “F*** no,” he said. “Don’t ever go back. You are so much better now. You are so much better.”

I don’t know what the way forward looks like — but I know it won’t be a way back. I can mourn my health. I can grieve. And I can also look towards a future in which I am wholly myself — however long or short it lasts.